In this chapter, Kitwood describes some of the processes that have been used to learn about what the experience of dementia may be like for people. This has led to the development of Kitwood’s flower which describes the main psychological needs of people with dementia. These needs inform the way in which we work towards maintaining the personhood of those living with dementia, and how we might use our resources, and for our purpose’s – music, to meet these psychological needs.

People with dementia have true subjectivity.

Intersubjectivity is about getting a sense of what another person may be thinking or feeling. We can do this through shared language, but also by a shared sense of body language: gesture, expression, posture, proximity etc. which help us to be surer of another person’s emotions.

Still, we can never truly know the full extent of another person’s experience. With dementia, there is a further limitation as nobody has ever “recovered” from dementia to explain to us what it is like. So, in dementia, more than in any other intersubjective experiences, we rely on inference. We use language to try to describe the experience of a state of losing our linguistic self. We try to capture concepts of the subjective world of a person who can no longer make sense of concepts.

Each person’s experience is unique. Generalisations are only guides, or signposts. Personality may be a factor in the way different people experience dementia.

Alan Jacques (1988) offered 6 personality types which may be useful to consider:

- Dependent: accept help readily, but perhaps reluctant to take initiative

- Independent: may resist facing truth about disabilities, like to feel in charge

- Paranoid: easily resort to suspicion and blame

- Obsessional: suffer with self-doubt, fearful of loss of order and control

- Hysterical: may be very demanding and attention seeking

- Psychopathic: very rare, impulsive, lacking signs of concern for others

These are not absolute, nor mutually exclusive.

Sean Buckland (1995) identified 6 main personality types in a small study of persons with dementia:

- Anxious-passive

- Stable-amiable-routine-loving

- Emotional-social-active

- Emotional-withdrawn-passive

- Stable-outgoing-industrious

- Emotional-outgoing-controlling

Again, not conclusive, nor mutually exclusive; but using personality type traits helps us gain some insight into how varied the experience of dementia may be for people.

During a person’s dementia journey, when resources are lost, grief reactions commonly occur. As with grief following a bereavement, certain patterns of experiences can be observed.

“Normal” grief stages in:

- Anger

- Denial

- Depression

- Acceptance

- Reconstruction.

Whereas in dementia, a sort of ‘pathological grief’ can occur, where the person becomes stuck in depression, perhaps reliving other griefs that were never resolved. The way each experiences these emotions is varied, as demonstrated above, particularly if a person moves into dementia with very little insight or processing. There is a strong case to made, therefore, for counselling and psychotherapy alongside diagnosis.

In this section, Kitwood offered seven possible ways we have gained insights into the experiences of dementia, highlighting once again the “uniqueness of persons” and each of their experiences.

1. Written accounts by people who have dementia.

This can shed a great deal of light at a time where cognition is relatively intact, but requires a potentially quite articulate, self-assured person.

The example below is from Living in the Labyrinth by Diana Friel McGowin, who among others describes ‘paralysing fears,’ relating to being abandoned, or her husband dying, feelings of guilt about her inability and dependency, her heightened sexual desire, and her development of obsessive behaviour to feel safe. Above all, her desire to remain a person.

Example 1.

“If I am no longer a woman, why do I still feel one? If no longer worth holding, why do I crave it? If no longer sensual, why do I enjoy the soft texture of silk against my skin? If no longer sensitive, why do moving lyric songs strike a responsive chord in me? My every molecule seems to scream out that I do, in fact, exist, and that existence must be valued by someone! Without someone to walk this labyrinth by my side, without the touch of a fellow traveller who understands my need of self-worth, how can I endure the rest of this unchartered journey?

(McGowin 1993: 123-4)]

2. Careful listening to what people say in interview or group work.

Various studies have been done which highlight issues such as fear of being out of control, and the fear of being seen by others as out of control; the feeling of being lost, and of meaning slipping away; the concern not to be burdensome and the desire to be useful; anger with dementia itself, and resentment that life has been marred by its presence. Some people express acceptance of their disabilities, and some their gratitude for the good things in their past.

There is a recurrent theme of reassurance through the company and support of others.

Rik Cheston (1996) explored the stories of people about their current situation, though interpretations are speculative, they can offer some ways that people with dementia describe their past.

Example 2.

“A man described episodes from his war service in Malaya, where he flew missions in the jungle. The persistent advance of the vegetation and the constant battle to keep it back seem to serve as a way for him to talk about his own struggle with neurological impairment.

A woman gave her account of being a nanny to two children during the ward and of the return of the father – thin, bewildered, and looking like someone who “had really lost his way.” Cheston suggests that she may be talking about her own condition: her own sense of lostness, her need for loving contact, and her desire to be of use to others, as once she had been as a nanny.”

3. Careful and imaginative attention to what people say during ordinary life. Expression may be different from everyday speech and meaning may be concrete, metaphorical or allusive. Often knowledge of the broader context of the person’s life and experiences gives meaning to their words.

Example 3.

“On a home visit with Peter, who had developed dementia in his 40s, he and his wife went to great lengths to be hospitable to me, and Peter talked in a rather fragmented way, about his life. He could remember some parts of his distant past, but he had no memory for many recent events. After some time, Peter took me for a walk round the garden. He took me to some lattice-type fencing, and began to feel it with his fingers. He told me that the older fencing was ery sound, but that some that had been put in more recently was already rotting; he showed me an example and crumbled a fragment in his fingers. I cannot prove it, but I felt sure that he was using this as a way of telling me about himself and his memory losses; it was like a repetition in tangible terms of our earlier conversation.”

“Janet has come into a residential home for two weeks’ respite care. She often looks out of the window and talks about the trains that are passing by. In fact there are no trains.

Her apparently strange remarks begin to make sense in light of the fact that she and her husband Roger often used to go by train to see their son and his family, who lived some 200 miles away. Roger still goes to visit them, and he does so when Janet is in respite care. Is it possible she has some inkling of this? Perhaps she is yearning to see her son, and asking to be taken too.”

4. Learning from the behaviours of people living with dementia – their actions or attempts at actions.

With dementia, a person will try to use whatever resources they still have available. If higher functions have faded away, it may be necessary to fall back on ways that are more basic, more deeply learned, some of these learned in early childhood.

Example 4.

“Arthur had been a highly respected member of the community, and a pillar of the local church. Now he is very confused and frail, and he is confined to a wheelchair. He often offends people with his foul language and some care staff are afraid of him, because when they come close he often punches or bites them.

It is possible that this is Arthur’s way of expressing his anguish at his loss of significance. Biting others may, almost literally, be his last way of ‘making his mark.”

5. Consulting people who have undergone illness with dementia-like features who may recall something of the experience, for example, meningitis and depression.

Example 5.

A woman with meningitis describes her memories of behaving in odd and unfamiliar ways like being told she had a received a visitor earlier in the day but, alarmingly, having no recollection of this; trying to say something but losing the sense of it like “a break in transmission”; playing cards but needing the rules explained each hand. Her account is filled with this sense of strangeness, weirdness, as if she both is and is not herself. She also spoke of the huge effort to do simple mental tasks.][Drop down depression example: A person with severe depression writes: “I’m frightened all day of the night to come because I know I’ll get restless and tense up, won’t be able to breathe, won’t be able to swallow, will start feeling numb and petrified – all the time I drum into myself that I’ve got to snap out of it. There’s far more going on in my head than what’s on paper, I just feel all the time there is a way to unjumble it all please somebody help me to find it.

6. We can use our own sense of poetic imagination to try to understand dementia. Some aspects of human experience are to complex and non-linear, and poetry can condense and make powerful understanding. John Killick spent many hours with people with dementia and wrote a series of poems expressing his attempt to respond to their hopes and fears.

Example 6.

3 short poetry extracts – the first a sense of weirdness and alienation, the second futility, and the third the pain of abandonment.

I’m sure it isn’t me

that’s gone round the bend.

It seems as if

I’m buzzing like a toy –

it buzzes round and round

but it doesn’t mean much.

You have hurt me,

You have hurt me deeply

Because you will go away

7. Role play – taking on the part of someone who has dementia and living it out in a simulated care environment.

If this is done with sincerity, flexibility and real commitment, we could learn a lot about the experience, both disturbing and enlightening: we might feel intense anxiety, fear of abandonment, generalized rage, the desire to create chaos, dreadful feelings of bewilderment, boredom, betrayal and isolation. Role play should always be done in a psychologically safe environment, with lots of time for debriefing and shedding of the role.

As we pull together evidence from these different sources, we begin to get a fuller picture of the experience of dementia. In particular, the difficult and painful aspects of the experience.

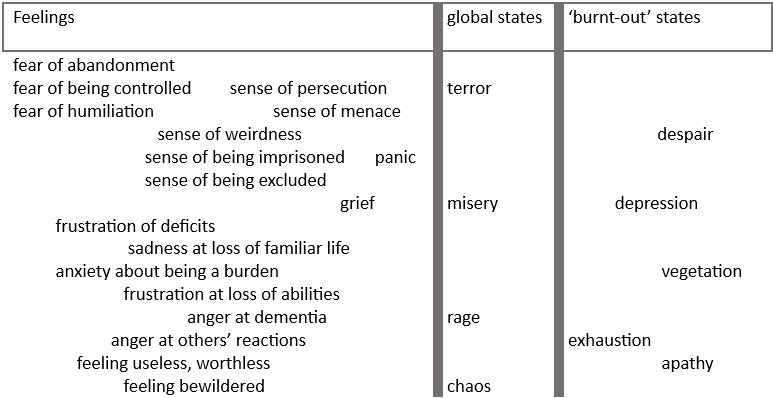

Figure 5.1 Domain of ‘negative’ experience

This map has 3 main areas:

Feelings

These are subjective states where emotions are clearly associated with specific meanings, e.g. anger at a loud neighbour, frustration at not being able to drive a car, or a sense of uselessness about not being able to clean the house. These feelings states remain available to people when cognitive impairment is low, when meaning-giving is still available. Though, of course, not everyone has a personal history of “feeling language.”

Global states

These are raw emotions associated with a high arousal of the sympathetic nervous system. This is the network of nerves which help to activate your flight, fight, freeze, fawn (immediately act to avoid the conflict) responses. Emotions in this category are not attached to specific situations, persons or objects. The “chaos” state refers to general confusion and may be attached to a lower arousal level as well.

Burnt-Out States

These typically occur when the body has been in high arousal for a long period, there comes a time when such intensity cannot be sustained. It is not necessarily a state of peace, but more one of severe depletion. The vegetative state that is claimed to be the end-point of the process of dementia lies at the extreme.

Apart, maybe, from those who are “burnt-out”, people with dementia can travel across these domains many times. Individuals will vary greatly in what they experience depending on their personality and their life experiences and hence their coping style. However, it is likely that at some point, when cognitions are severely impaired, raw emotions will break through with intensity. A few may be able to sustain their defences and pass slowly through to the burnt-out area. The intensive use of tranquilizing medication may be seen to promote such a process.

The dark picture of dementia described in the domains of experience tab probably represent a situation where psychological needs are, at best, only poorly met. This subjective exploration plus evidence from objective studies, helped Kitwood to develop a picture of what these needs are.

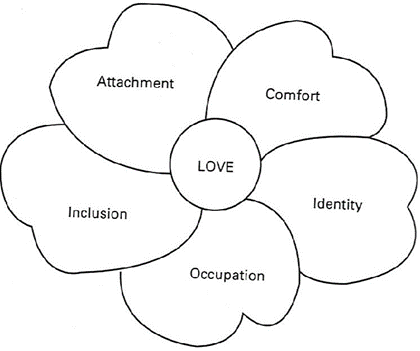

Figure 5.2 The main psychological needs of people with dementia

Comfort

This word carries meanings of tenderness, closeness, the soothing of pain and sorrow, the calming of anxiety, the feeling of security which comes from being close to another. To comfort another is to provide warmth and strength, which might help them to remain in one piece. In dementia, this need may come to the fore when a person is dealing with loss, or parting. The heightened sexual desire could be seen in part as a manifestation of this need.

Attachment

Ours is a highly social species. John Bowlby (1979) claimed that bonding is cross-cultural, universal and instinctual. It creates a kind of safety-net especially in our earliest years. Without the reassurance that secure attachments provide it is difficult for any person, of whatever age, to function well. It may be that the need for attachment remains as strong for people with dementia as in early childhood. People with dementia are continually finding themselves in situations that they experience as ‘strange,’ and this powerfully activates the attachment system.

Inclusion

As a social species, we have evolved to be part of group, it was essential for our survival, and in some cultures, exclusion from the group a type of severe punishment. The need for inclusion come to the surface in dementia, perhaps in so called ‘attention-seeking’ behaviours, in tendencies to cling or hover, or in protest or disruption. If this need is not met, a person is likely to decline and retreat. When the need is met a person may be able to ‘expand’ again, have a distinct place in the shared life of a group.

Occupation

To be occupied means to be involved in the process of life in a way that is personally significant, which draws on a persons strengths and abilities. The roots of this are found in infancy, that developing sense of agency that we can make things happen in the world. The need for occupation is still present in dementia, clearly manifested when people want to help, or eagerly take part in activities and outings. It requires skill and imagination to meet the need without imposing false solutions, crude and ready-made. The more that is known about a person’s past, their sources of satisfaction, the more likely solutions will be found.

Identity

To have an identity is to know who you are in thought and in feeling. It means a sense of continuity with the past, a narrative or story to present to others. Much can be done to preserve identity in dementia. Two essential things: to know in some detail about a person’s life history, and the second is empathy. This allows us to respond to a person as uniquely them.

Consider the personality types and traits that we learned about here – is it helpful or not so helpful to think about this when considering how some of the people you may work with present in their dementia journey?

Why might that be?

It can be useful to remember that people who are living with dementia are people with personalities, and lived experiences, that may inform the way that they respond to the challenges they face in their dementia journey. This in turn can help us think about how we offer our support or understand some of their challenges

Reading the 7 different ways that Kitwood used to understand some of the different experiences of dementia, did any of these stories strike a chord?

Could it inform the way we listen to the people we support?

In music therapy, as in these descriptions from Kitwood, we understand that all behaviour is communication: the disjointed speech, or self-stimulating actions, to more aggressive behaviours. The people we support are communicating – as best they can – a need, and with careful listening and attention, it may be possible to discern what that need may be.

Tom Kitwood, regarding person-centred care in dementia support, highlighted the psychological needs which he felt needed to be met for an individual to feel well and cared for, these include Attachment, Comfort, Inclusion, Occupation and Identity.

How might music be used to try and meet these various needs?

For example, singing regularly with someone might strengthen a relationship (attachment), bringing a sense of security and familiarity to the interactions.

The use of familiar music and music that is meaningful to the individual, that brings back positive memories, delivered in a reliable and predictable way (e.g. at the same time every day) may help to provide a source of comfort.

Taking part in group music-making may assist with feelings of inclusion, being part of something in a ward or care environment, particularly when music is something accessible that most people can engage in regardless even in late stages of dementia.

Active music-making, if done in a meaningful way, in a way that is relevant to the individual can provide a source of occupation, which is thought to be essential for good mental health and wellbeing.

Using preferred music, music related to country of origin, music associated with significant events in someone’s life can all contribute to reinforce an individual’s sense of identity, which may be becoming more fragmented as memories fade.

Can you think of someone you know or work with who is living with dementia and identify some of the needs they may have according to this model?

It can be helpful to note your thoughts and feelings down for you to reflect on later.